Anna Daučíková, Artist

In 1968 I was 18. In Czechoslovakia there was, like many other places, a hippie movement. There was the Iron Curtain and we were isolated, but still we had information and there was a youth movement where sexuality was set free.

But I have to say, and this is my criticism of the 1960s, is that this sexual revolution was a revolution for heterosexual men and those women who were able to go with them. There was a certain sexual freedom, which I could call bi-sexuality, but this bi-sexuality had a condition and the condition was that there had to be a man and then you can be free. So I think that this time, which is now idealized and described as this time when people were completely free, is not all true. There is a dark part to it, which was that women had to be obedient to the imperative of making love to a man. If you were “in”, then you were someone who was able to make love freely with a man.

When I was going to school at the Academy of Fine Arts there was a student exchange program between the schools from the satellite countries and the schools in Soviet Union. When I had an opportunity to travel to Soviet Union as a student I immediately did. I returned every summer working in either Kiev or Moscow and I moved there in the late 1980s.

People in Soviet Union, generally, had less prejudice about sexual life then here in Czechoslovakia. Divorce was a normal thing. It was not strange that someone was married three times. They had a different moral structure then we did. In this way it was totally secular. The propaganda of the nuclear family and the reality of what was happening were completely different. I think that the society in the Soviet Union were much more benevolent then in the satellite countries where they (the government) had to be like dogs on guard to make sure that there was not a counter revolution. In the center of the system they could be easier with some things and one of these things was sexuality and marriage.

It was normal for people of the same sex to hold hands. Straight people were holding hands and men were kissing and hugging hello and goodbye. In Bratislava if men had been kissing it would have been a scandal. There, it was not homosexual it was just culturally normal. And, many people understood same sex relationships as love. The only condition was love. If you love it was moral. If you don’t love, don’t do it. At the same time, there was in the Soviet Union a law against same sex relationships so you had to be somewhat careful or you could go to prison.

I moved back to Bratislava in 1992 and met a group of woman working at the Slovak literature magazine, Slovenske Pohlady. Together we started to read and talk about Feminism. From these meetings we started the organization Aspekt and brought feminist ideas to the public. Aspekt did not deny lesbians a voice in the feminist movement. This was very courageous for the founders because gay rights were still very much taboo at the time and it did not help their careers to be so accepting. They were even more courageous than me because I had nothing to lose.

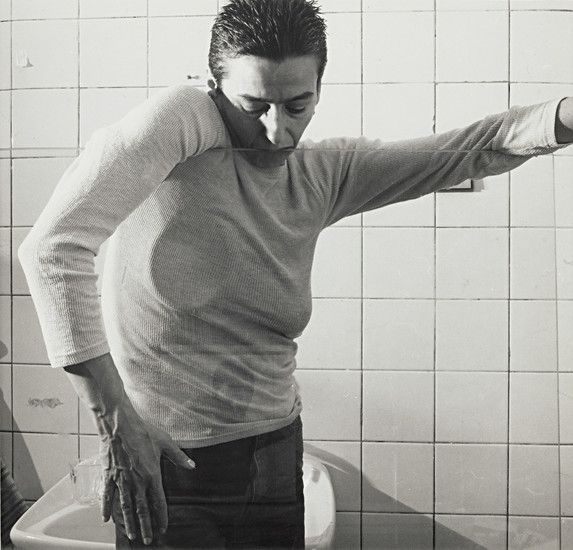

Anna Daučiková, Educate by Touch, 1996

In the late 1990s the Vatican asked the Slovak government to sign a treaty that, among other things, protected the role of the family. When you read it closely you understand that this is a ban on gay rights and gay partnerships (it was signed in November 2001). Because of this, a group of us came together and decided to be the spoke persons for gay rights. We called ourselves Initiative Difference. Our first objective was to make public the aims of this treaty through the media. I have to say that the media was absolutely fantastic during this time. They were not biased against us, but gave us the same amount of space and coverage as they did to the other side.

I think that one of the most positive and constant things in Slovakia during these past 20 years is the development and role of progressive and open-minded journalists. Of course there are many points of view in the media, but there has consistently been a strong voice that is pro-democracy.

The other thing that has developed is that it is more and more okay, and this has really developed in the past ten years, to be gay. In the '90s you would never see gay people holding hands on the street and now you can see it. People are much more open. Today the gay community is more stratified. You can find the different layers of society and different points of view and world opinions. You can really choose your community within the community and this is very important. So it is getting better. There is still a long way to go and a lot of work to be done, but it is getting better.

This interview was in English

Photo by Janeil Engelstad